Introduction

Why do “identical” parts still come out different? Variation starts at the cut. Die cutting turns a design into consistent cuts, creases, and perforations. A die cutting machine makes it repeatable.

In this guide, you’ll learn how it works, how methods differ, and what to ask before you run.

How Die Cutting Works on a Die Cutting Machine

How a shape becomes a dieline

A die cut job starts as a dieline. It is a “map” for the cut and crease. It includes cut lines, crease lines, and perforations. It may also include kiss-cut lines for labels. Good dielines reduce scrap and delays. They also make quoting faster, since suppliers can estimate waste and tooling.

Most teams build the dieline in CAD or Illustrator. They keep each action on its own layer. They also lock the dieline layer before export. This prevents last-minute shifts and bad registration. If you want the long-tail answer, this is it: how to make a dieline for die cutting starts by separating actions and naming them clearly. It also means using clear units and scale notes.

What’s inside the cutting stack

Die cutting uses controlled force through layers. The basic stack is simple. It has the material, the die or cutting tool, and a cutting plate or pad. Flatbed systems press down. Rotary systems pinch through cylinders. In both cases, clearance and pressure set edge quality. A stable stack keeps cuts uniform across the sheet or web.

If pressure is too low, cuts stay incomplete. If pressure is too high, plates wear fast. You may also see crush marks on paperboard. Many sheet systems use durable frames and hardened guide rails to keep pressure stable (needs verification). Stability is the difference between clean cuts and constant tweaks. It also helps when your job has fine details and tight corners.

What die cutting can do besides cutting

Die cutting is more than “cut out a shape.” It can crease cartons for folding. It can perforate tear lines. It can emboss logos for a premium feel. It can also do steel rule die cutting for thicker packaging boards. These actions can happen in one pass, which saves handling.

Kiss-cut is common in labels. It cuts the face stock, not the liner. Through-cut goes through both layers. Each action needs its own pressure target. That is why you must label dieline actions clearly. It also helps to note which side faces the die, since coatings can crack on the wrong side.

How feeding and registration keep parts accurate

Feeding decides accuracy at scale. A sheet-fed die cutting machine relies on consistent grippers and guides. A roll-fed line relies on web tension and edge guiding. Both use registration marks to correct drift. If marks shift, your cut shifts too. Even small drift can ruin a printed window or border.

For printed work, registration is critical. A small error becomes obvious on logos and windows. Teams often test the first sheets, then lock settings. They also monitor heat, dust, and vibration during long runs. Those factors can push registration off slowly. If you run films, humidity and static can also change feed behavior (needs verification).

How waste is removed after cutting

After cutting, you must remove waste. In labels, this is matrix stripping. In packaging, it is blanking and stripping. The waste “web” can tear on sharp corners. It can also tear on thin bridges in the design. That is why rounded corners help. Smooth paths reduce snag points during stripping.

Better layouts also reduce waste. Nesting shapes can raise yield. But tight nesting can worsen stripping. You must balance yield and removability. Good converters treat stripping as a design constraint, not a cleanup step. They also plan for waste rolls and disposal, since adhesive waste can be costly.

How operators validate quality before full production

A die cutting machine should never jump straight to full speed. Teams run test cuts first. They check cut depth, crease quality, and registration. They then adjust pressure, shims, or timing. Only then do they ramp to production speed. This routine prevents long runs of scrap.

They also track simple metrics during the run. They watch scrap rate, edge quality, and dimensional drift. They swap worn plates before they fail. This approach keeps output stable, even on long shifts. It also protects tooling life, which lowers long-run cost.

| Step | What Happens | What to Check | Common Risk |

| Dieline prep | Build cut/crease/perf lines | Layers, naming, scale | Wrong line type, wrong version |

| Stack setup | Material + die + plate/pad | Plate condition, clearance | Overcut or incomplete cuts |

| Feeding & registration | Sheet or web feeds consistently | Guides, tension, marks | Drift and misregistration |

| Test cuts | Run first samples | Cut depth, crease quality | Scrap ramp-up |

| Waste removal | Strip/blank waste | Matrix tearing, snag points | Sharp corners, thin bridges |

| Production run | Ramp speed and monitor | Scrap rate, drift, wear | Wear causes slow quality drop |

Die Cutting Methods Compared: Flatbed, Rotary, Semi-Rotary, Digital

Flatbed die cutting for thicker sheets and packaging

Flatbed die cutting presses a sheet under a platen. It can deliver high force and clean creases. It works well for cartons, corrugated, and rigid boards. It also supports larger formats for retail displays. Many packaging lines like it because setup is easy to see and verify.

A flatbed die cutting machine fits short to mid runs. It also fits packaging prototypes when you need real creases. Setup takes time, but it pays back on repeat jobs. If you run paperboard often, flatbed is a safe baseline. It can also handle thicker stacks where rotary would struggle.

Rotary die cutting for fast roll-to-roll production

Rotary die cutting runs continuously on rolls. It is built for speed and repeatability. It is common in labels, tapes, foams, and films. It also supports high-volume industrial converting. For many B2B lines, it is the workhorse for stable SKUs.

A rotary die cutting machine shines on long runs. Tooling cost can be higher, but unit cost drops fast. Web handling becomes the main skill. If tension control is weak, waste rises quickly. If your material stretches, you may need closed-loop control (needs verification).

Semi-rotary die cutting for flexible label workflows

Semi-rotary uses a rotary die, but it indexes. It can cut complex repeats with less waste. It is popular in label converting. It also supports frequent job changes. Many teams like it when order sizes vary week to week.

It helps when you need flexibility. It can also reduce material waste on short repeats. If your orders vary often, semi-rotary can protect margins. It also supports faster changeovers in many shops.

Digital die cutting when you need speed without tooling

Digital die cutting uses blades or lasers. It needs no physical die. It is great for sampling and quick changes. It also fits low-to-medium volume work. It reduces tooling risk when designs keep changing.

Digital is not always cheaper. It can be slower per unit on big runs. Edge finish may differ by material. For packaging teams, it is a strong prototype tool. Many call it a digital die cutting machine for packaging prototypes, and that fits well. It also works for short marketing runs with many versions.

Quick comparison table

| Method | Best for | Typical materials | Setup cost | Unit cost at scale | Speed | Notes |

| Flatbed | Cartons, thicker sheets | Paperboard, corrugated | Medium | Good | Medium | Strong creasing, solid control |

| Rotary | High-volume roll work | Labels, films, foams | High | Best | High | Needs strong tension control |

| Semi-rotary | Variable label jobs | Labels, films | Medium | Good | Medium-High | Often reduces waste |

| Digital | Samples, short runs | Paper, thin boards, films | Low | Higher | Low-Medium | Great for fast iteration |

Die, Tooling, and Machine Parts That Affect Results

Die types and what “custom die” really means

A die is the cutting tool that matches your shape. Packaging often uses steel rule dies. They are knives set in a board. Labels often use flexible dies for rotary systems. Some jobs use solid dies for long life. Each type affects lead time and edge quality.

“Custom die” means lead time and repeat cost. It also means you must lock the dieline. If you change the shape later, you may pay again. That is why teams prototype first, then commit. It also helps to keep version control, so the shop runs the right file.

Plates, pads, shims, and pressure control

Plates and pads take wear. They protect the machine and the die. Shims fine-tune clearance. Small changes can shift cut depth. Over time, plate wear changes results. If you ignore wear, you will chase settings all day.

If you see incomplete cuts, pressure may be low. If you see burrs or crush marks, pressure may be high. If you see uneven cuts across the sheet, leveling may be off. Good maintenance keeps these issues rare. It also keeps your cut edges consistent across batches.

Machine features that drive speed and repeatability

A die cutting machine is not just force. It is control and rigidity. A stiff frame reduces vibration. Stable guide rails reduce drift. Reliable clutch and brake behavior improves timing. Consistent feeding improves registration. These features matter more when you run thin films or tight tolerances.

Automation also matters. Computerized controls can speed setup and reduce human error. Central lubrication can cut downtime (needs verification). These features matter most on long runs and tight tolerances. They also help new operators reach stable output faster.

Safety features that matter in daily operation

Safety is not optional in production. Many systems use emergency stops, guards, and interlocks. Some add limit switches for position control (needs verification). These features prevent accidents and reduce damage during jams. They also protect tooling and reduce surprise downtime.

They also protect uptime. A safer process means fewer stoppages from near misses. It also supports audits in regulated industries. In some plants, safety design is a purchasing requirement.

Materials You Can Die Cut and Typical Applications

| Material / Product | Common Use | Recommended Method | Notes |

| Paperboard cartons | Folding packaging | Flatbed | Crease quality is critical |

| Corrugated displays | Retail POP | Flatbed | Needs stable pressure |

| Labels (face + liner) | Stickers, branding | Rotary / Semi-rotary | Kiss-cut requires liner control |

| Films | Protective, functional | Rotary | Tension and guiding matter |

| Foams / EVA | Cushioning, seals | Rotary | Nesting vs stripping balance |

| Tapes | Bonding, masking | Rotary | Adhesive residue needs checks |

| Gaskets | Sealing parts | Rotary / Flatbed | Inner holes need clean edges |

Packaging: cartons, corrugated, retail displays

Packaging needs consistent creases. A carton must fold cleanly and close square. Die cutting combines cutting and creasing in one pass. That reduces handling and misalignment. It also improves fit on automated packing lines.

Paperboard thickness and coating affect results. Coatings can crack on sharp creases. Teams often adjust crease rules and pressure. They also test fold lines early. This prevents late-stage rejection. For high-end cartons, even small cracks can cause returns.

Labels and stickers: kiss-cut vs through-cut

Labels often use kiss-cut. It keeps the liner intact. It also speeds application in production. Through-cut is used for sheet stickers or parts. The choice affects how you strip waste and how you ship parts.

Adhesives change everything. Some adhesives “ooze” under heat and pressure. That can lift edges later. Liner stiffness also affects stripping. If you do kiss cutting labels, you must test face stock and liner as a set. You should also test peel behavior after 24 hours (needs verification).

Industrial converting: foams, tapes, films, gaskets

Industrial parts need tight shapes and clean edges. Foams and tapes are common. Films can stretch if tension is wrong. Many gaskets need consistent inner holes and outer edges. Common uses include sealing, cushioning, and insulation.

Rotary die cutting is common here. It handles continuous webs well. Nesting layouts can improve yield. But too-tight nesting can tear during matrix removal. The best layout balances yield and stability. Many teams also plan for roll width and core size to reduce changeovers.

Harder or trickier materials and how to approach them

Some materials are harder to cut cleanly. Thick plastics can burr. Soft rubber can deform. Some composites can delaminate. These issues need process changes, not just pressure. If you only increase force, you may damage the stack.

Teams may use sharper tooling, different die angles, or slower speed. They may also switch method. A flatbed press may handle thick sheets better. A rotary line may handle films better. Material behavior should guide method choice. It also helps to test different hardness levels and coatings.

Design and Dieline Checklist for Cleaner Die Cutting

Dieline file setup that printers and converters expect

A good dieline file reduces back-and-forth. Keep cut, crease, perf, and kiss-cut on separate layers. Use clear spot colors and names. Lock the dieline layer before final export. Export in the format your converter requests. This avoids guessing on the shop floor.

Also include a note on scale and units. Add key dimensions on a separate layer. This helps quick verification. It also avoids “silent” scaling errors during file handoff. If you revise the dieline, change the version label in the file name.

Bleed, safe zones, and tolerances that prevent rework

Printed work needs bleed beyond the cut line. It hides small cut shifts. It also prevents white edges on color blocks. Safe zones protect text and icons from being cut. These rules are simple, but they save costly reprints.

Tolerance depends on method and material (needs verification). Many teams plan for a small shift and design around it. They also avoid tiny text near cut edges. This is cheap insurance. If your brand colors are critical, consider adding a stroke or background buffer.

Shapes that cause tearing or distortion—and how to redesign

Some shapes fail during stripping. Sharp internal corners can snag. Thin bridges can tear. Tiny holes can fill with dust and cause rough edges. Acute angles can deform soft materials. These failures are predictable once you see a few runs.

Fixes are often simple. Add small radii to corners. Widen bridges. Simplify paths. Avoid ultra-thin features unless needed. These changes can cut scrap fast. They also make tooling last longer.

Prototype strategy: when to test digitally vs order a die

Prototype choice should match risk. Use digital cuts for early geometry checks. Use physical dies when creasing and fit matter. For packaging, physical samples often reveal fold issues early. It also reveals how coatings behave on creases.

A common approach works well. Iterate digitally until the dieline is stable. Then order the die for real testing. After approval, scale production on the chosen die cutting machine. This keeps both speed and confidence.

Prepress checklist table

| Item | Why it matters | Quick rule |

| Separate action layers | Prevents wrong tooling | Cut / crease / perf split |

| Spot colors for dielines | Keeps lines readable | Use clear names |

| Bleed beyond cut | Hides small shifts | Add bleed (needs verification) |

| Safe zone inside cut | Protects text | Keep text inside buffer |

| Rounded corners | Helps stripping | Add small radii |

| First-article sample | Catches failures | Approve before full run |

Cost, Speed, and Quality: How to Choose the Right Die Cutting Machine

When die cutting beats hand cutting in real ROI

Hand cutting works for very low volume. It fails when volume rises. It also fails when shapes are complex. Die cutting wins when repeatability matters. It also wins when labor is expensive. It reduces rework, since parts match each other.

A simple decision rule helps. If you cut the same shape often, use a die. If you change shapes daily, consider digital. If you run labels at scale, consider rotary. Match the method to the business model. Also consider delivery time, since tooling lead time can matter.

Tooling cost vs unit cost: what changes with volume

Physical dies add setup cost. They reduce unit cost on repeat runs. Digital has low setup cost. It can keep unit cost higher at scale. That tradeoff drives most buying decisions. It also affects your quote strategy.

You can model it fast. Total cost = setup + (unit cost × quantity). Compare methods at your expected quantity. The break-even point often appears quickly (needs verification). This prevents “cheap machine” mistakes. It also helps you decide if you should outsource early runs.

Waste and yield: how layout and process choice save money

Waste is hidden profit loss. Layout drives yield. Nesting can reduce waste. Grain direction can affect fold strength in paperboard. Matrix stripping can force extra spacing. If you ignore yield, your per-unit cost will drift up.

Process choice matters too. Rotary can reduce handling waste. Flatbed can reduce distortion on thick sheets. Semi-rotary can reduce waste on short repeats. Ask your supplier to show a yield plan, not just a speed claim. A simple nesting mockup can reveal big savings.

Quality metrics you can measure on the shop floor

Good teams measure quality, not opinions. Track dimensional accuracy. Track edge quality. Track crease depth consistency. Track registration accuracy on print. Track scrap rate per shift. These metrics let you compare methods fairly.

These metrics link to cost directly. They also help improve setups over time. They reveal whether issues come from material, tooling, or machine settings. They also support supplier claims during audits.

Setup, Maintenance, and Troubleshooting for Reliable Production

Setup steps that prevent bad cuts from the start

Start setup on the real material. Confirm the dieline version matches the die. Set pressure gradually, not all at once. Verify registration marks early. Check crease quality by folding samples. This reduces surprises after ramp-up.

Also confirm waste removal behavior. Strip the matrix on test pieces. Watch for tearing and lifting. Adjust layout or pressure before you ramp speed. This prevents long runs of bad parts. If you run adhesives, check for residue buildup early.

Fast fixes for common die cutting problems

Many problems have repeat causes. Incomplete cuts often mean low pressure or worn tooling. Crush marks often mean high pressure or plate wear. Misregistration often means feed issues or mark reading problems. Tearing often means sharp corners or thin bridges. Treat symptoms as signals, not mysteries.

Use a quick diagnostic table. It speeds training and keeps output stable.

| Symptom | Likely cause | Fast fix |

| Incomplete cut | Low pressure, worn die | Increase pressure, inspect die |

| Crush marks | High pressure, worn plate | Reduce pressure, replace plate |

| Misregistration | Feed drift, mark error | Check guides, verify mark sensor |

| Matrix tearing | Sharp corners, tight nesting | Add radii, loosen spacing |

| Burrs/rough edge | Tool dull, wrong clearance | Sharpen/replace, shim adjust |

Maintenance routines that reduce downtime and scrap

Maintenance is cheap compared to scrap. Keep plates clean and flat. Inspect wear parts on a schedule. Monitor lubrication routines. Clean dust and adhesive residue often. Replace worn pads before they fail. These steps keep settings stable.

On automated systems, check sensors and guides. Small misreads can cause big shifts. Keep a simple log of adjustments. Over time, it becomes a playbook for faster setups. It also helps you spot recurring issues tied to one material or die.

Operator habits that improve safety and consistency

Operators shape results every day. They should follow lockout rules during jams. They should never bypass guards. They should keep hands away from feed zones. They should stop the machine when cuts drift. These habits prevent accidents and protect tooling.

They should also run process checks. Sample parts at fixed intervals. Record scrap causes. Share notes between shifts. This keeps the die cutting machine stable across teams. It also helps new staff learn faster.

Conclusion

Die cutting shapes materials at scale and delivers clean cuts, creases, and perforations with consistent results. The best method depends on volume, material, and tolerance: flatbed works well for cartons and thicker sheets, rotary fits high-volume rolls and labels, semi-rotary supports flexible label jobs, and digital helps with fast prototypes and short runs. A practical next step is to confirm the application and material, prepare a clean dieline and checklist, run first-article checks, then scale production once settings stay stable.

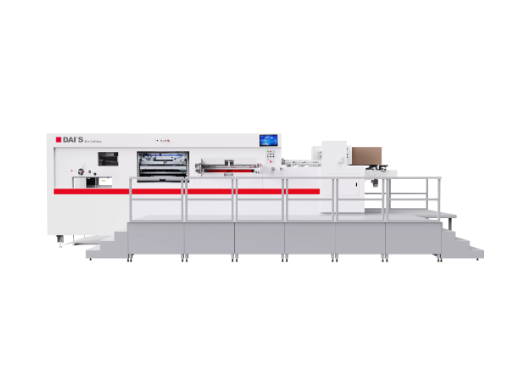

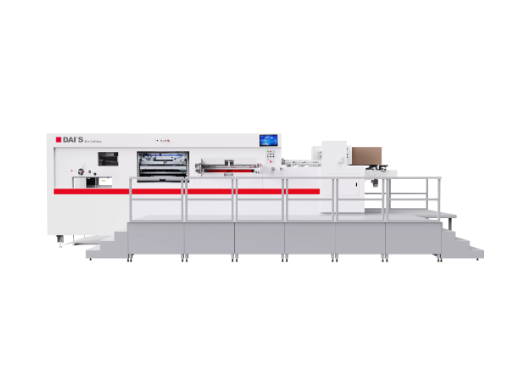

Daishi Printing Machinery Co., Ltd. provides die cutting machine solutions that focus on reliable control, repeatable output, and production efficiency, helping buyers reduce scrap and keep cost predictable.

FAQ

Q: What is die cutting and why use it?

A: It shapes parts fast and consistent, often on a die cutting machine.

Q: How does a die cutting machine work in one pass?

A: It presses a die through a cutting stack to cut or crease.

Q: What’s the difference between flatbed and rotary die cutting?

A: Flatbed suits thick sheets; rotary runs rolls fast on a die cutting machine.

Q: What is kiss-cutting in labels?

A: A die cutting machine cuts face stock, not the liner, for clean peeling.

Q: What affects die cutting cost most?

A: Volume, tooling, waste, and setup time on a die cutting machine.

Q: Why do cuts come out incomplete or rough?

A: Pressure, wear, or shims may be off on the die cutting machine.